Why China's Rise Might Not Be Peaceful — by Prof. Jin Canrong (Part 2)

"History shows that the establishment of new institutions and norms is almost always accompanied by violent measures." - Jin Canrong

This is the second instalment in a series of hawkish commentaries on China’s foreign policy by the popular international relations scholar Jin Canrong. Readers may also refer to our first instalment, which dwells on what Jin perceives critically as the pacifist tendencies of China’s elite. It is accompanied by a prefatory note from Prof. William A. Callahan. — James

Key Points

If China is to establish new global norms and institutions, it is reasonably likely that violence will be necessary—history shows this nearly always to be the case.

From a diplomatic perspective, Beijing’s choice of the term “peaceful development” is pragmatic, as phrases like “peaceful rise” tend to arouse apprehension among other states.

However, an exclusive emphasis on peace is inconsistent with the realities of what may be required for China’s rise. The term should therefore be avoided in academic analysis.

Though peace is preferable to war, denying the possibility of conflict is self-deceptive, muddling serious research and constraining China’s strategic options in the future.

Three-Year Anniversary Special: 12 months for the price of 6.

Exclusively for current subscribers—offer ends in a week.

Support this non-profit newsletter and unlock exclusive content.

In the context of Sino–Japanese relations, the rise of Japan’s far-right Sanseitō and mainstream resistance to China’s 3 September Victory Day parade underscore that peace is far from assured.

Although Japan might portray itself as a victim by highlighting the suffering of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, it is China that stands as the true “victim of history”.

Japan is therefore unlikely to embrace China’s historical narrative voluntarily, and admonishing it for a lack of self-reflection is ultimately futile.

Once China achieves overwhelming economic and technological advantage over Japan, it will be able to let “strength do the talking” in resolving future disputes.

The Author

Name: Jin Canrong (金灿荣)

Born: Dec. 1962 (age: 62)

Position: Wu Yuzhang Chair Professor, School of International Studies, Renmin University of China (RUC); Director, Centre for China’s Foreign Strategy Studies, RUC

Other positions: Special research fellow at the Research Office of the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress; Consulting expert for various ministries and government departments; Director of the China International Public Relations Association (the list goes on)

Previously: Researcher at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (1987-2002)

Research focus: American politics; US-China relations; Chinese foreign policy

Education: BA Fudan University (1984); MA University of Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (1987); PhD Peking University (1999)

Experience abroad: Several stints in the United States as a visiting scholar (1990s)

WITHOUT HEGEMONY, NO STATE COMMANDS FEAR—CAN CHINA DEFY THIS POLITICAL RULE?

Jin Canrong (金灿荣)

Published on Jin Canrong’s Public Account (金金乐道编辑部) on 26 September 2025

Translation by Jan Brughmans

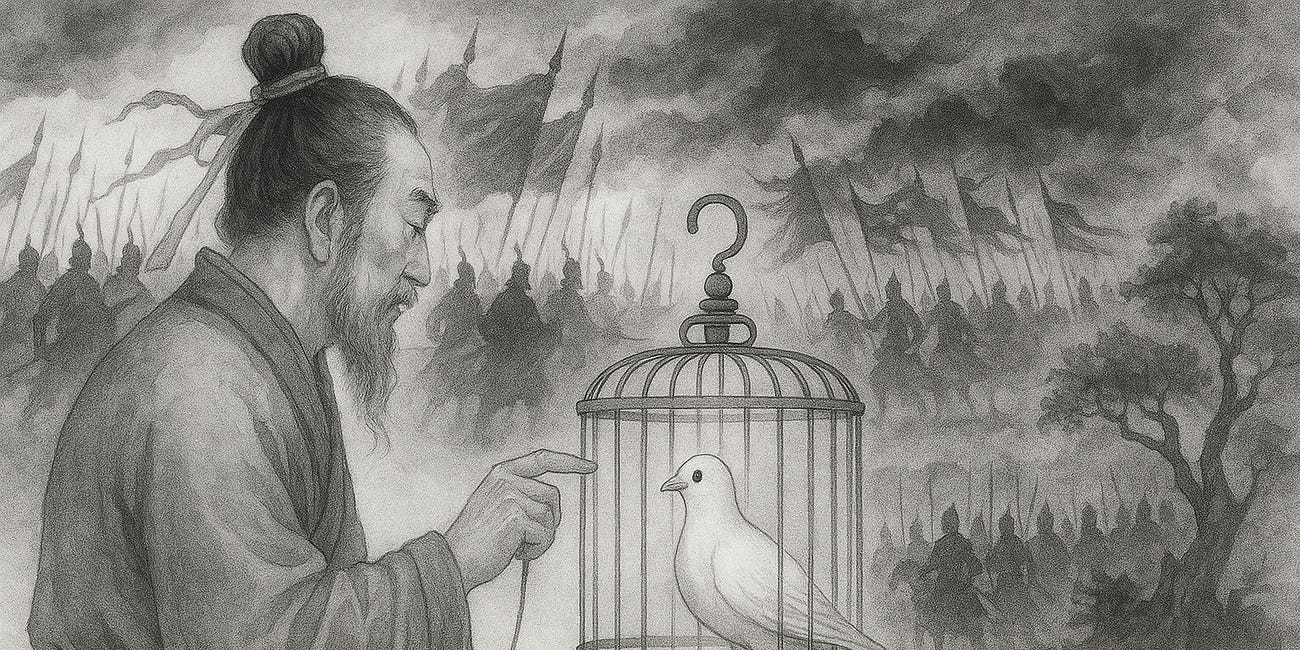

(Illustration by OpenAI’s DALL·E 3)

Truly, among today’s great powers, China is the one that most firmly adheres to the path of peaceful development—it is China’s basic national policy [基本国策]. Yet nowadays, we are confronted with a problem: throughout the history of humankind, examples of major powers rising peacefully are exceedingly rare.

Human nature contains both a rational side and a relatively pronounced irrational side. Across history, the rise of nearly every great power has been accompanied by war: the US is no exception. In 1898, the US deliberately provoked conflict, launching war against Spain and seizing Cuba, Guam, the Philippines and other territories. Strikingly, Spain at the time had almost entirely yielded to US demands and was willing to kneel or prostrate itself at command—utterly submissive [百依百顺], it is fair to say. And yet, the US still chose to give them a good hiding [揍它]. Given all this, whether China can achieve national reunification and realise the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation without recourse to war remains, frankly, a bit of an unknown quantity [未定之数]. On certain issues, we may have no choice but to demonstrate our strength.

My own view of history is this: violence constitutes the underlying logic of historical motion [暴力是历史运行的底层逻辑]. What distinguishes human beings from animals is the possession of institutions, but the establishment of institutions is ultimately inseparable from violence. Economic activity unfolds within the framework of institutions, and all economic behaviour must adhere to political norms; otherwise, it reverts to primitive economic forms.

For China to rise, it must set up its own institutions [制度] and norms [规范] within the international community. However, history shows that the establishment of [new] institutions and norms is almost always accompanied by violent measures [离不开暴力]. Can China truly escape this historical pattern? I have my doubts. The Chinese are human beings too and, no matter how capable, cannot transcend the basic laws of human society. We will, of course, strive to rely on our own diligence and ingenuity to achieve development, but on problems of fundamental national interest [涉及国家根本利益], we must also be prepared to “flex our muscles” [秀肌肉] when necessary.

In the early period of reform and opening-up, we advanced the concept of “peaceful development” [和平发展]. Subsequently, as development achieved results, at least a portion of the international community came to acknowledge the reality of China’s rise. Yet if we continued to purely emphasise “peaceful development”, it would have become increasingly difficult to respond to outside concerns regarding China’s growing strength.

It was against this backdrop that some domestic scholars put forward the concept of a “peaceful rise” [和平崛起]. Simply put, within our overall framework of “peaceful development”, we acknowledge the reality of China’s “rise” while at the same time emphasising its “peaceful” character. At the time, however, many senior diplomats objected, arguing that this was an unwise move [并非明智之举]: the term “rise” was too provocative and so could easily heighten tension and vigilance in the international community. Consequently, the central government ceased using this expression and reverted to the formula [提法] of “peaceful development”.

In terms of diplomatic strategy, it may have been a wise approach to avoid unsettling the outside world. Yet in serious academic research and strategic analysis, this adjustment warrants reconsideration. In truth, it seems more like a self-deceiving [掩耳盗铃] attempt to avoid ructions [矛盾]. Such a reluctance to squarely face up to reality cannot stand up to scrutiny [站不住脚]. We often say that the core of Mao Zedong Thought is to seek truth from facts [实事求是]. By denying the facts and literally violating this principle, research—regardless of how in-depth it is—lacks an adequate starting-point. No matter how correct [正确] one’s standpoint might be, to have elided the facts is enough to deny all of one’s subsequent conclusions. As such, weighing up our real interests, we can’t make any absolute guarantees on whether China can carry out its rise peacefully. We must first recognise the fact of China’s rise, while making clear that we will conscientiously strive to achieve it peacefully. However, we should not make any absolute promises about a “peaceful rise”. After all, any absolute promise risks tying our hands [成为束缚自身的枷锁].

The above are merely my tentative reflections—simply one school of thought [一家之言], offered up for reference. Please do not misunderstand me: I have no intention whatsoever of drumming up support for war [笔者绝无鼓吹战争的意图].

THESE STATEMENTS FROM JAPAN ARE EXTREMELY MALICIOUS

Jin Canrong (金灿荣)

Published on Guancha.cn (观察者网) on 27 August 2025

Translated by Jan Brughmans

According to reporting by Japan’s Kyodo News, the Japanese government has asked countries across Europe and Asia not to attend China’s military parade and other events next week held to mark the 80th anniversary of victory in the War of Resistance against Japan.

The Japanese government’s request for Eurasian countries not to participate in China’s related commemorative events is extremely detrimental to Sino-Japanese relations. The 3 September Military Parade carries not only commemorative significance but—even more so—value for self-reflection [反思价值]. Rather than taking this opportunity to think on its sins [深刻反省自身], Japan has chosen to create obstructions, revealing its continued lack of genuine willingness to confront historical issues. Eighty years on, Japan has neither come to terms with this chapter of history nor approached it with honesty. Instead, it has sought to cast itself as a “victim”, treating the Hiroshima and Nagasaki memorials as an arena to broadcast the blows that it received. Never does it pose to its citizens the question: why did Japan face such devastation in the first place? While lacking the correct attitude to this history, Japan is bound to repeat its historical mistakes [重蹈历史覆辙].

In recent years, far-right forces and ideologies have been steadily gaining ground in Japan—a trend that demands serious vigilance. In the House of Councillors election held in July, the far-right political party Sanseitō, founded only five years ago, increased its representation from just two seats to fifteen. Former Japanese Ambassador to China, Tarumi Hideo, went so far as to state that as China’s power continues to grow, Japan should refrain from confrontation for the time being and wait until China declines before making a move against us. Such remarks are profoundly malicious! [Note: This interpretation of Tarumi’s remarks was echoed in the English-speaking sphere by China International Communications Group (CICG)]

It is extremely difficult for China to compel Japan to confront its past; we neither possess such capability nor should we entertain such expectations. We should not persist in telling Japan’s right-wing, “You need to do some serious self-reflection”. For a long time, China hoped that Japan would eventually come to terms with its history. Yet in reality, those hopes were always somewhat unrealistic.

As a victim of history [历史受害者], we must always remember this period, learn its lessons, firmly seize opportunities for development, and dedicate ourselves resolutely to strengthening our nation. As for Japan, our stance should remain straightforward: whether it chooses to reflect on itself or not is its own decision. We love and cherish peace, but if Japan still wants to act the fool [还想犯浑], then in the end we should let our strength do the talking [就靠实力说话].

Why did modern China fall behind? Why were so many countries able to invade it? Why did Japan dare to launch a full-scale war of aggression? The fundamental reason lies in the fact that China’s industrial strength [工业实力] at the time lagged far behind that of the West. After the founding of the People’s Republic of China, Chairman Mao correctly identified this core contradiction and devoted immense effort to driving industrialisation, ultimately creating the largest industrial system in the world. It is precisely because we have built this comprehensive industrial base that we no longer fear any adversary.

Today, we must further consolidate our industrial advantages and, building on this strong productive capacity, develop more advanced military and technological capabilities. We have repeatedly urged Japan to reflect on its history, but since it refuses, so be it. If, in the future, conflict [矛盾] between China and Japan at any point erupts, we will resolve the matter through absolute strength [绝对实力].

Judging by current trends, the balance of power between China and Japan is gradually returning to its normal historical state [历史常态]. Kenichi Ohmae, a highly influential Japanese management theorist, once observed that, from the standpoint of geography and the deep complexities of its historical civilisation, China is the natural central power of East Asia. For much of the past century, Japan was able to serve as the region’s economic hub largely because it industrialised first, securing an overwhelming advantage over China. Ohmae also pointed out that industrial strength is, at its core, an advantage in knowledge. Once China committed itself to mastering the knowledge essential for industrialisation, surpassing Japan became only a matter of time. Once China’s technological capabilities have reached parity with Japan’s, the decisive factor is scale. Ohmae predicts that by 2049, China’s economy will be ten times the size of Japan’s.

I concur with Kenichi Ohmae’s assessment. Provided China avoids major strategic missteps [不犯重大战略错误] and sustains its current rate of industrial and technological progress, achieving a GDP ten times that of Japan by 2049 is entirely feasible. By that point, whether Japan chooses to confront its history or not will no longer matter. For the Chinese people, we must never place our hopes in Japan voluntarily facing its past—let them do what they like [他们爱咋咋地]. Once our strength has become absolutely overwhelming [形成绝对碾压], addressing these [historical and political] issues will be far easier.

READ MORE

Jin Canrong on the "Peace Disease" among China's Elite (Part 1)

To an outsider, the idea that China suffers from a “peace disease” and still follows Deng Xiaoping’s “hide your brightness, bide your time” policy seems far-fetched, especially in view of Beijing’s massive military parade in 2025 and the PLA’s daily challenges to Taiwan’s air and sea space.

But again, the value of the articles lies not in their content, but in their position in Chinese strategic debates. Since liberals are scarce in the PRC, Jin is telling other nationalists that they need to be even more strident. He’s also worried about a backlash in China that is not just popular, but populist. That is, the Chinese elite is worried about growing popular resentment that is not just directed externally at the West and Japan, but also internally at the Communist Party.